Interview by Simon Sellars

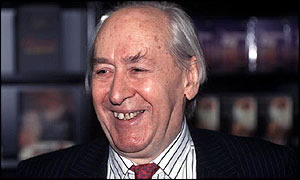

JG Ballard. Photo: Paul Murphy.

Originally published on ballardian.com, 29 September 2006.

In the year that this website’s been in operation, it seems to have had a momentum — a secret logic — all its own. Our interviews with such luminaries as Bruce Sterling, John Foxx, Mike Ryan and Iain Sinclair — even the irascible Jonathan Weiss — have been undisputed highlights, but in hindsight they were clearing the ground for the ultimate statement of intent: a conversation with J.G. Ballard. With the release of Kingdom Come, Ballard’s new novel, it suddenly struck me: we can’t keep orbiting around the sun forever. I had to speak to the man — especially since KC represents some of his most interesting work for a long while.

Kingdom Come’s set up is classic Ballard: its narrator, Richard Pearson, is drawn into the suburban London town of Brooklands after learning of his father’s murder in the Metro-Centre — a huge, ultra-modern shopping mall. But Pearson proves to be most unlike Ballard’s passive, ambiguous narrators of old. A former adman — now bored, jobless, and disaffected — Pearson becomes embroiled in the dark undercurrents brewing in Brooklands’ sport-and-product obsessed social strata. Manipulating to power and pulling the strings of a ‘third-rate Fuhrer’, Pearson oversees the seccession of Brooklands as a ‘shopping republic’, before setting off a post-consumer apocalypse and violently torching the landscape.

The negative notices this remarkable vision have received don’t make a whole lot of sense to me. Here’s a man who admits he doesn’t read novels; instead he devours ‘invisible literature’: marginalia, copywriting, medical journals, psychiatric reports, Ikea catalogues. He’s influenced by Freud, film noir, science fiction and Surrealist paintings; film, more than anything. To compare him with some literary type who practices the art of ‘tight plotting’ and ‘well-rounded protagonists’ is woefully inadequate. Reviewing KC in the Telegraph, David Robson wrote: ‘The plotting is clumsy … and the violence, integral to the whole design, belongs to the world of comic-strips’. Well, yes. Precisely. Honestly, do we still live in an age where popular culture is considered second-rate to the almighty ‘novel’? Funnily enough, it’s Robson rather than Ballard who puts me in mind of my 78-year-old father, who refuses to watch The Simpsons because ‘cartoons are for kids’.

The novel is still largely a 19th-century form which has completely excluded … any consideration of the impact of science and technology on human beings from the main body of its work … most mainstream 20th-century novelists are still working with a 19th-century form that’s concerned not with dynamic societies but with static societies where social nuance is still important”.

———————————————————-

J.G. Ballard, quoted in C21 (1991).

———————————————————-

The cable channels had reverted to an anaesthetic diet of household hints and book-group discussions. Once people began to talk earnestly about the novel any hope of freedom had died.

————————————–

J.G. Ballard. Kingdom Come.

————————————–

In some ways I felt liberated conducting this interview by phone from Australia. It meant that I didn’t have to make the pilgrimage to Shepperton on the motorway before being deposited at JGB’s door, where I would be admitted and compelled to comment on the Ballardian nature of the journey. Nor would I feel compelled to comment — as so many do — on his run-down semi-detached house that’s in dire need of a paintjob. Or the objects on his bookshelf that haven’t moved in 30 years. (As JGB told an interviewer in 2003, “Please! Don’t ask me about the dust! Everyone is fascinated by my dust — there must be more interesting things to talk about”.) I wouldn’t need to ask — as so many have before — how Ballard’s childhood in Shanghai shaped his fiction, before expressing surprise that such a grandfatherly figure could produce such a nightmarish vision. (Actually, Jeffrey Dahmer looked pretty average, too. So what?).

I know I would have done all of that. How could I resist? The media has preserved in aspic this avuncular image of JGB for so long now — right up until the recent KC press — that it’s no wonder ‘Pearson’, the Ballard proxy, is so fed up (remember, Ballard is also an ex-copywriter). No wonder he feels like blowing up everything he’s ever created and wandering off into an uncertain future.

No — ensconced on the other side of the world, I felt I could safely ask J.G. Ballard what really makes him tick.

——————————————————————————————————————-

Simon Sellars

——————————————————————————————————————-

SIMON SELLARS: I’ve been keeping up with the Kingdom Come reviews: people are criticising you for repeating the template of your last three novels. But it seems to me you’re actively parodying your own style.

J.G. BALLARD: I think there’s an element of that. But I think there always has been in my novels. I can’t resist having a dig at myself.

A character describes Pearson as ‘beyond psychiatric help’.

Ah yes – that is a deliberate little in-joke for those who are interested. The publisher’s reader for Crash made that comment years and years ago, so I couldn’t resist inserting it.

[The reader’s famous verdict: “This author is beyond psychiatric help. Do not publish”].

Perhaps the most obvious shift in your style occurs in Pearson himself: he’s more active in shaping the events around him than equivalent characters in previous books.

The thing is, I wanted the protagonist — the narrator — to be more involved professionally, and emotionally, in the events that are unfurling. If you go back to my previous novels, something like Super-Cannes — the narrator of that finds himself in this strange business park in the south of France by chance, really, whereas the narrator in Kingdom Come

is directly involved. I wanted to show how disaffected and deracinated intellectuals often get drawn into political conspiracies that turn out badly. We have a clear example at the present time with many of the leading American intellectuals who are involved with President Bush and his neo-cons — someone like Fukuyama, although I think he’s recanted. These think-tank intellectuals in America provided a lot of the rationale for the whole neo-con response to 9/11. And earlier than that, you see people like Joseph Goebbels — a fully-fledged intellectual, without any doubt — becoming the propaganda chief of the Nazi regime. Albert Speer’s another one. I wanted to show how rootless intellectuals do get involved in these conspiracies.

And so we have Richard Pearson — this advertising man, who’s been trying to liven up the advertising business with a bit of psychopathology and has failed — arriving at this huge shopping mall and seeing a chance to put his theories into practice. He finds David Cruise, a third-rate Fuhrer running a cable-TV show and gets to work, not realising quite what he’s doing.

The reviews have been mixed.

They haven’t been all that great, to be honest. There have been some good ones, but on the whole they’ve been rather downbeat. And that’s something one just has to live with. But also I just get the vague feeling that this is a subject that the sort of people who review books would rather not look at too closely. Perhaps I’m deluding myself, there, but after all, Kingdom Come is a full-frontal attack on England today. I think in many ways this country has lost its direction, lost its purpose, and there are some very strange things going on under the surface. And that’s what I’m writing about — I have been for years.

The book’s themes travel beyond England, though.

Well, my feeling about this country — that we have nothing left but consumerism — does, as far as I know, translate to other consumerist societies like America and Japan. My impression is that Australians, however, have got other things to do with their spare time. They’re not besotted with shopping, because the country’s so large and there are so many opportunities for recreation — that’s probably another delusion of mine, I’ve no idea. But I’ve been to Canada several times and no-one would call Canada a consumerist society, because people have got more things to do — there’s more space. The peculiar thing about England is that we’re so densely populated. When I say there’s nothing to do except go shopping, that’s almost the truth. You know, you can’t climb into your car and drive off into the wilderness. Shopping is all we have. But I think, translated overseas, the general principle of Kingdom Come will hold: there is something about consumerism and late capitalism that is too close for comfort to fascism. There are echoes.

Carradine pointed to the concourse. On a circular plinth stood three giant teddy bears. The father bear was at least fifteen feet tall, his plump torso and limbs covered with a lustrous brown fur. Mother and baby bear stood beside him, paws raised to the shoppers, as if ready to make a consumer affairs announcement about the porridge supply.

—————————————

J.G. Ballard. Kingdom Come.

—————————————

‘Play with us’ — bears at the Bentall Centre, the real-life inspiration for Kingdom Come’s Metro-Centre. Photo by Joanne Murray.

Well, we like to indulge in a little cathartic violence in Australia, too. I don’t know if you heard about the riots on Sydney beaches last year…

Oh yes, I did. Rival gangs attacking immigrants.

Kingdom Come resonated with me because its clockwork mobs were so reminiscent of this incident. Except instead of football, it was organised around surfing — a typical Aussie touch.

I think sport is the key catalyst. England doesn’t have a very good soccer team, but we’ve always had world-class hooligans. And I think the English take a certain pride in that.

Why is that? To compensate for loss of Empire?

I’m not sure it has anything to do with that. The British Empire was lost a long time ago, and most British people didn’t benefit directly from Empire. In fact, there are economic historians who claim we made a loss from the British Empire — that it cost more than we gained from it. Most British people didn’t share in the Empire at all, and I don’t think the loss of all these possessions scattered around the world was a tragedy for the British. It was probably a relief when it collapsed. It’s like when you read accounts of the Republican movement in Australia, which has my 100% support, of course…

Mine, too.

I can’t understand why an English queen is the Australian head of state. It’s bizarre. I mean, why not have a Japanese head of state? A Swedish head of state? I can see that there are ties to Britain, and perhaps one shouldn’t make light of these things, but most English people wouldn’t be in the least bit upset if you decided to have your own head of state and declare Australia a republic. I don’t think the end of Empire is such a big thing, now. It might have been true thirty or forty years ago, but not now.

I had seen the flag as I drove into the town, the cross of St George on its white field, flying above the housing estates and business parks. The red crusader’s cross was everywhere, unfurling from flagstaffs in front gardens, giving the anonymous town a festive air. Whatever else, the people here were proud of their Englishness, a core belief no army of copywriters would ever take from them.

—————————————

J.G. Ballard. Kingdom Come.

—————————————

Off Edenham Way, Notting Hill, London. Photo by Simon Crubellier.

Nationalism, though, plays a big part in the events you describe in Kingdom Come. Same as with these beach riots: they were propelled by an intense nationalism — republicanism taken to its logical extreme.

Well, that does happen, doesn’t it? People will seize on any symbol or banner or slogan that comes in handy. Like here, during the World Cup a couple of months ago: English supporters seized on the St George’s cross, a flag that was virtually unknown ten years ago. It was only when the National Front, the ultra-right party, started draping themselves in the Union Jack that the possibility that a flag might sum up one’s ambitions came into play. I live in a very quiet suburb, absolutely docile, and a couple of years ago — it may have been during the European football championship — I looked out of an upstairs window and saw that two of my neighbours, about 100 yards away, had erected flagpoles in their garden and were flying the St George’s cross. It sent an odd feeling down my spine, because it was clearly saying something. You don’t go to the trouble of buying a flagpole — and these were real flagpoles, much taller than the bungalows next to them — and then put a big flag on it without it meaning something. I wouldn’t even know where to buy one!

At Ikea, perhaps? Surely the 2005 riots at that shrine to consumerism were another influence on Kingdom Come.

Well, the Ikea riots happened when I was writing the book. ‘There we go,’ I said to myself. Yes — that was an incredible event in many ways. It fed into the novel. England is a much more socially divided, unstable and violent place than people realise. This is not some sort of Switzerland floating in the North Sea. We’re not a Scandinavian country, like Norway or Sweden. We ought to be part of that bloc, but we’re not. I don’t know what we are. That’s the problem.

Spending had a strong social incentive, and the desire to be the highest spender in the neighbourhood was given moral enforcement by the system of listing all the names and their accumulating cash totals on a huge electric sign in the supermarket foyers. The higher the spender, the greater his contribution to the discounts enjoyed by others. The lowest spenders were regarded as social criminals, free-riding on the backs of others”.

——————————————–

J.G. Ballard. ‘The Subliminal Man’ (1963).

——————————————–

Kingdom Come’s theme of violent consumerism seems to be an update of some of your earlier work — I’m thinking of your short stories ‘The Subliminal Man’ and ‘The Intensive Care Unit’.

Those stories were so long ago… Yes, perhaps there are elements in them. Maybe you’re right. I hadn’t thought of it.

Your short stories are just superlative. Why don’t you write them anymore? I think that’s an aspect of your work that is deeply missed by many people, including myself.

The problem is that there’s nowhere to publish them. Very few magazines or newspapers these days carry them. It used to be very common in the English papers 50 years ago — some papers had a short story every day. But also, if you’re going to write them, you’ve got to cast your mind into the short-story mode and think in terms of short stories. You can’t just turn that on for one piece. Every so often I get rung up by a newspaper or magazine, and they say ‘We’re doing a special number with three or four short stories, specially commissioned. Would you write one?’ But they want something very short to start off, and mine tend to be much longer, and then they want something rather conventional — something that’s not going to unsettle the advertisers. Well, I’ve tried to devote my entire career to rattling other people’s cages and it’s difficult to do that these days with a short story.

A company of beautiful women moves through the palatial corridors or gazes into the opaque depths of ornate mirrors, waiting for a last act that will never unfold. Even those women who are naked seem scarcely aware of themselves, as if their sexuality is defused by the strange bedrooms where they wait for the rich and powerful men stepping from their limousines in the courtyards below”.

——————————————–

J.G. Ballard. ‘The Lucid Dreamer’ (on Helmut Newton; Bookforum, 1999).

——————————————–

In our Iain Sinclair interview, Sinclair said that ‘Kingdom Come could have been stripped down to be a series of savage essays or presentations about the motorway corridor with dramatised events happening in the middle’. I started thinking along similar lines: perhaps your non-fiction writings — the short journalistic pieces you do for newspapers — have taken on the characteristics of your short stories.

Yes, I think there’s a germ of truth in that. I mean, people have long complained that my book reviews have nothing to do with the book in question! And that’s something I apologise for, because it’s extremely irritating to the author.

You once said the key image of the 20th century was the car. What do you think the key image of the 21st century will be?

That’s interesting. It’s hard to tell — it’s so early. If I had to pick an image now, it’d probably be an internet screen. It obviously plays a big part in peoples lives. But it’s pretty early — contact me in 50 years’ time and I’ll update that!

An image from the Japanese Gallery of Psychiatric Art.

I’m not hooked up to the internet, which is rather bad of me. I write all my books in longhand – don’t believe all this stuff I say about technology! My girlfriend has a PC and a modem, but we don’t seem able to connect it up. But I love the idea. My dream would be to download the entire Harvard University database, or to consult every psychiatric journal ever published. However, I’m terrified that if I do get the modem working, I’d never do anything else!

——————————————————————————————————

— JG Ballard, ‘JG Ballard Live In London’, Sub Dee Magazine (1997).

——————————————————————————————————

I found myself in London in 1996 for a talk you were giving, and I remember you saying your dream would be to hook up to the net and download every psychiatric journal ever published.

Lovely thought.

So, it’s nine years later — have you done it yet?

No. I don’t have a PC. I’m not on the internet and I think that’s a matter of age. I’m nearly 76 now and I think the personal computer and the internet really came in about 10 years ago. And by then I was an old dog and the internet was a new trick. I mean, I still write my novels in longhand and type them out on an old electric typewriter. I don’t have any modern appliances. I have a mobile phone but I hardly ever use it. And all these things like iPods and Blackberries – I am interested in them, but I’m too set in my ways.

The ‘environmental disaster’ theme of your earlier work doesn’t get namechecked as much as the ‘urban disaster’ themes in your later work. Why is that?

I suppose it’s because the kind of urban disaster imagery that I wrote about in Atrocity Exhibition, and Crash

, and High-Rise

is closer to people’s lives. Not many people have visited a jungle recently, or a desert. People are very concerned about ecological damage to the planet, but it tends to be something you see on television, whereas decaying, inner-city ghetto blocks, high-rise blocks and car crashes are part of everyday life if you live in a big city in the west — or in the east, for that matter.

As the sun rose over the lagoon, driving clouds of steam into the great golden pall, Kerans felt the terrible stench of the water-line, the sweet compacted smells of dead vegetation and rotting animal carcases.”

——————————————————-

J.G. Ballard. The Drowned World (1962).

——————————————————-

But the ecological vision in your earlier work is getting a bit too close for comfort, though. The aftermath of Hurricane Katrina was reminiscent of The Drowned World.

Yes, it did remind me of Drowned World. An extraordinary event, really — that something like that could happen to the most advanced nation on Earth.

How do you feel about having your own dictionary adjective — ‘Ballardian’?

I’m surprised, actually, but I suppose it’s a compliment. It’s a shorthand phrase, but the trouble with shorthand phrases is that they often conceal more than they state. Take a term like Orwellian: it immediately sums up 1984, but of course there was a lot more to George Orwell than 1984. In fact, most of his books are not ‘Orwellian’. Animal Farm is not Orwellian in the sense that 1984 is. But, no — it’s a huge compliment. I do take it as a compliment.

According to Collins, ‘Ballardian’ is defined as ‘resembling or suggestive of the conditions described in JG Ballard’s novels & stories, esp. dystopian modernity’. But surely your writing is far too playful to be branded dystopian. I find your characters and situations affirming, for all the darkness they willingly surround themselves with.

I’m glad you said that. I think my work is superficially dystopian, in some respects, but I’m trying to, as you say, affirm a more positive worldview. I lived through more than two-thirds of the last century, which was one of the grimmest epochs in human history — a time of unparalleled human violence and cruelty. Most my writing was about the 20th century, and anyone writing about the 20th century writes in a dystopian mode without making any effort at all — it just comes with the box of paintbrushes.

You know, to be a human being is quite a role to play. Each of us wakes up in the morning and we inhabit a very dangerous creature capable of brilliance in many ways, but capable also of huge self-destructive episodes. And we live with this dangerous creature every minute we’re awake. Something like The Atrocity Exhibition sums up my fiction: the attempt by a rather wounded character — in this case, a psychiatrist having a nervous breakdown; there are similar figures throughout the rest of my fiction — to make something positive out of the chaos that surrounds him, to create some sort of positive mythology that can sustain one’s confidence in the world. Even something like Kingdom Come is affirmative, where I show a clear and present danger being dealt with, and one of the key figures responsible realising the error of his ways. So in that respect, I agree with you completely: my fiction is affirmative.

Mr Ballard indulging in the ‘Playboy lifestyle’. Screenshots from Crash! (1971), dir. Harley Cokliss.

Playboy thinks so, too. Did you know that they recently voted Crash the fifth sexiest novel of all time?

Who said that?

Playboy magazine.

Playboy?

Yes.

Playboy magazine?

Yes!

You mean Hugh Hefner’s magazine?

Yes — Hugh Hefner!

Good God! I’m amazed.

Me, too.

I’m genuinely amazed.

It came in at number 5.

Well, I take that as a compliment. Usually, crashing expensive sports cars would not figure highly in the Playboy lifestyle. What you want instead is a glamorous blonde in the seat next to you and a martini cooler in the rear seat as you drive at 150 miles an hour. And no talk of crashing!

What do you know about the film of High-Rise that Vincent Natali’s working on?

I think it’s in the early stages of development. I think there is a script, and they’re still working on it. ‘In development’ in the film world generally means that they’re looking for the money. We’ll see. I’ve seen Natali’s Cube and I liked it. I thought it was original. I think he can bring something fresh to the idea.

Before I knew Natali had signed on, I remember seeing Cube and thinking he’d do a great job filming High-Rise. The themes and obsessions seemed to parallel your book.

Yes, very similar. I agree with you.

What other films have you seen recently?

Oh… Well, I live in a small town called Shepperton, with just a single high street and about 40 shops, two of which were DVD and video rental stores. I patronised them regularly — I used to see about three films a week. I was tremendously up with what was going on in the film world, but over the past couple of years, both those stores have closed down. And this means that I’ve stopped renting. So I’ve hardly seen any films at all for a long while. I mentioned this to someone recently, and she said, ‘Ah, this is because people are downloading films from…’ I couldn’t make out what she was talking about, actually — from their mobile phones, it sounded like. Downloading from somewhere — they don’t need to go to video stores anymore. I also think people are moving into a kind of post-TV, post-film world, where they’ve got so many other things to do. Recreation of every conceivable kind. The idea of passively watching a screen seems to be passing. I think that part of the appeal of the internet is that it’s interactive — an obvious thing to say, of course. But also, films are so bloody awful these days.

And just plain bloody, too. What do you think of this trend towards horror films that depict hyperreal scenes of torture and sadism? Films like Wolf Creek, Hostel, Severance, and so on.

Horrible. I’ve never liked horror films.

Why?

Oh, I don’t know. Fear of death or something. The earliest horror films I saw were Dracula movies — never liked those. The whole idea of horror, particularly wrapped up in touches of the occult — ugh. They’re saturated with the fear of death and displaced sexual anxieties. No, thank you. Not for me.

Well, they’re much more sadistic these days. It really is ‘violence as spectator sport’ — to quote yourself.

Absolutely. You see this dimension of anatomical frankness even in popular TV programs like CSI. Every one ends with a cadaver being cut up, and a heart or a brain being removed and held up to the light. Pretty frightening stuff. But I think we’re anesthetised — our sensibilities are dulled. There may be all the frankness on this screen, but most people, in England anyway, wouldn’t have seen a dead body, let alone an autopsy. Put it all down to the diseased brain that helps to run human affairs.

I know you feel differently about science fiction: you once said it was ‘the only true literature of the 20th century’. What about today?

Well, the problem is that at the heart of science fiction was novelty: it was predicting the new all the time. I remember reading science-fiction magazines from the 1950s and one was constantly excited by the vision of the future dominated by television, advertising, space travel — the modern world, in short. As far as I can see, science fiction has lost that sense of the new, because its vision has materialised around us. We take it for granted. The future envisaged by science fiction is now our past, and the result is it’s probably come to a natural end. That doesn’t mean that one can’t continue writing it: one just has to move into a different terrain.

A psychogeographical terrain? There’s a recent book that has co-opted you into the psychogeographical literary movement.

I’ve seen that book. It doesn’t apply to me. No, that’s Iain Sinclair’s terrain.

You once said you were becoming more left-wing as you got older. Does that still fit?

I think it probably does, actually. I don’t know about Australia — it strikes me as a pretty wonderful place, from everything I’ve read about it — but here, the gap between rich and poor is widening to such an extent that, particularly in London, it’s begun to shift the whole demographic. The middle class, the people who sustain modern society — the nurses, junior doctors, teachers, civil servants and so on — are being forced out because vast sums of money are pouring into the housing market and distorting it. Gated communities are springing up everywhere, and the moment they can, people are opting for private medicine, private teaching, private hospitals — cutting themselves off from the rest of society, and that’s not a healthy development. One thing I’ve always liked about America, and I think it’s probably true of Australia, is that the children of well-to-do people and the children of people on modest incomes go to the same schools. I think that’s good. It’s not true over here and that’s bad! A class-ridden society with huge divisions — that’s bad. Something ought to be done about it, but I’ll leave that to another generation.

Well, things are becoming more divisive in Australia. Our Prime Minister wants to test immigrants for ‘Australian values’: it’s worryingly undefined so it could be anything — Australian slang, Aussie songs and so on — as the PM has hinted. Maybe people will be deported if they can’t say ‘you bewdy’ or talk like Steve Irwin with conviction.

God.

Things are changing all over.

And not necessarily for the better.

Mr Ballard, many thanks for your time.

It’s been a pleasure.

————————————————————————————————-

Many thanks to Mally Foster and Helen Ellis at Harper Collins; Mel Chilianis for the tech set up; J.M. Rudder for the films; Simon Crubellier, Paul Murphy and Joanne Murray for permission to use their photos; Andres Vaccari, Raymond Tait, Ben Austwick, Chris Nakashima-Brown and Tim Chapman for invaluable research assistance; and Bruce Sterling, Mike Ryan, John Foxx and Iain Sinclair for their thoughts on Ballard.

————————————————————————————————-

…:: LINKS

+ Review by Steven Shaviro Praise the Lord — an intelligent review of Kingdom Come for a change

+ An Evening with J.G. Ballard

+ Bruce Sterling on J.G. Ballard

+ Mike Ryan on J.G. Ballard

+ Jonathan Weiss on J.G. Ballard

+ John Foxx on J.G. Ballard

+ Iain Sinclair on J.G. Ballard