Photo: Simon Sellars.

Melbourne artist Juan Ford is on a hot streak, his recent paintings blending innovative technique with spiritual enquiry, unlocking the unfathomable mysteries of human existence. Aligning his work with recent debates on the ethics of cloning, Ford attempts to bring religious debate into the – quite literally – “soulless” technological era. If there is such a thing as a soul, he challenges, what happens to it when we eventually get round to cloning humans: will the clone be an empty copy, devoid of this spiritual life force? Or can our souls be replicated, stamped out in endless versions?

Ford splits his human subjects in two and leaves them to fend for themselves amid geometric, biomechanical landscapes and grids, the visual language of computers, dreams and technology in overdrive. The results are playful and wise, tinged with a little melancholy…

Originally published at Sleepy Brain, 25 April 2003.

You studied engineering but never finished the course. How did you lever yourself from that to becoming a full-time painter, arriving at your particular “photorealistic” style?

It’s a really stupid story. When I was about 20 I liked to draw. A friend of mine had started up a shop selling basketball cards. These cards were “in” for a while and he was cashing in on that and we were in class together. He said to me, “Here, take these magazines, they’ve got pictures of Michael Jordan in them. I want you to draw Michael Jordan for these cards”. And I thought, “Yeah, why not? I haven’t drawn for a while”. Suddenly I’ve got these photoreal, quite good drawings of Michael Jordan and it took me completely by surprise that I could do this.

So that was enough incentive to give engineering away completely?

Yeah. Plus I started hanging around with Fine Art students and they were more fun.

Today, photorealism is still characteristic of your work. What appeals to you about this technique?

It’s not just about mimicking photographs. In fact it’s really difficult to describe. These paintings take a long time to do and demand a lot of concentration. You get an incredible sense of satisfaction when you pull it off and I guess that’s the motive. There are all sorts of theoretical considerations in doing what I do but my interests aren’t just limited to photorealism. I’ve done installations involving cylindrical anamorphosis, where you put a cylindrical mirror on top of an image that’s been manipulated and the image comes up clearer in the mirror, when it didn’t prior to that. I like to use a lot of visual, spatial tricks.

Anamorphosis is another key component of your visual style and a device you draw on heavily. Could you describe the principle to someone who may have no understanding of what it might involve?

You know when you’re riding on a bike and you come across the stretched-out bike symbol in the bike lane? That’s anamorphosis. When you’re riding and looking down on it, due to the way perspective behaves, it actually contracts to become a pretty clear symbol. But if you looked at it directly above, it would be really stretched out. It’s the distortion of an image so that it has to be seen from a particular angle to make sense. There’s other types of more advanced anamorphosis, where you have to use special mirrors curved in certain ways, for example.

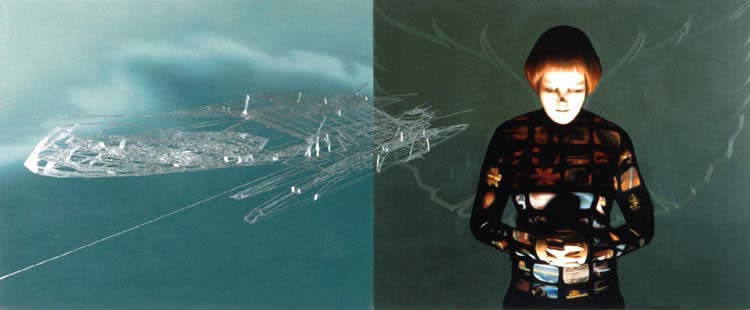

Chrysalis (2001) 2400 x 1000.

‘This is my partner, Emily. I asked her what she most desired and it was “opportunity”, so I put these stylised wings behind her symbolising that. When you put your face next to hers, you see this anamorphic shape turn into a wire-frame satellite. The satellite symbolises the search for opportunity.’

You engrave your anamorphic visuals onto and aluminium. How did you arrive at this combination of material and technique?

This all came out of my Masters project, which looked at how to combine anamorphosis with realism. What I was doing in all my Masters paintings was asking each of the sitters what it was they most desired. As an additional metaphor I would engrave through the materials I was painting on. Originally, this was masonite and so I’d cut through the masonite patterns that were anamorphic and that was like a metaphor for revealing the sub-strata, the very basic thing which is like the innermost desire of the human subjects. And then I thought, “Well, what else can I try?” I’d painted on aluminium once before when I was at art school and thought, “Yeah, I’ll try painting on aluminium and then engraving through it”. It looked fantastic and so I’ve stuck with it, even though its more of an effect now – a sort of trademark signature.

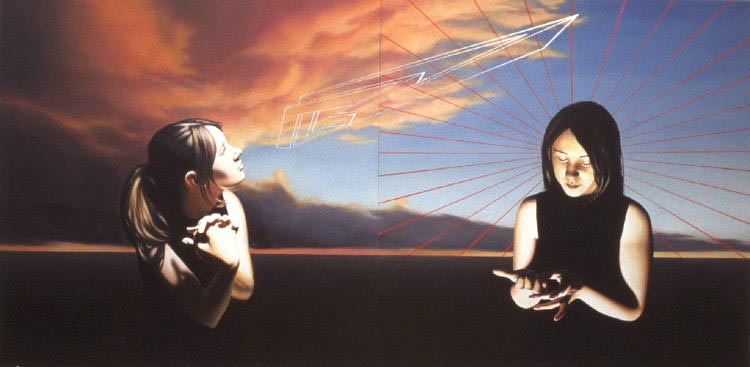

Assumption & Delusion (2002) 2400 x 1200.

‘This painting is of Lauren, who I went to art school with. One “Lauren” looks vainly at her fingernails, the other at the sky in rapture. All the works from the Clone series are in this super-flat, definitely unreal computer landscape.’

I respond to the science-fictional aspects of your work, particularly your Clone series. This tone of yours seems to come from dreams, or from a strategically located social experience…

It comes from many places, from playing computer games a lot and just generally being brought up in a generation that’s been exposed to a lot of science fiction. And yes, certain ideas have come from dreams. I used to have this recurring nightmare where I would up in this completely white place where I couldn’t see…

A white room?

Well, I knew it was something very expansive, but I couldn’t see the difference between sky and land and it was really frightening. I tried to put those super flat planes and landscapes in many of my paintings.

Is this some kind of archetype? I wonder if you’ve seen George Lucas’s first film THX 1138? Your dream automatically reminds me of a scene toward the very end, where dissidents in a future dystopia are imprisoned in an expansive white room, with white ceiling, floors, walls, clothing. It’s like they’re snow-blind, unable to see…

It’s in a lot of films, actually. In terms of archetypes, it’s been described as “the ego being afraid of death”.

Do you still dream it?

Not so much. I have the dream occasionally, but I’m no longer afraid of it for some reason.

Alpha (2001) 2400 x 1200.

‘This painting, along with Omega, is about beginning and end, birth and death – the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet. I’d left the desire thing behind and wanted to do something else. Here’s Masato Takasaka, an artist who’s quite big in Melbourne, in a Van Halen shirt screaming, with this completely white background from the dream I told you about. I took the original photo at night on a wet road, which becomes a metaphor for a journey beginning. Next to Masato is this very strange shape, a Klein bottle – the physical equivalent of a Moebius strip. The inside of the bottle becomes the outside…’

Omega (2001) 2400 x 1200.

‘This painting, along with Alpha, is about beginning and end, birth and death – the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet. Here, my friend Rebecca is pretending to be dead on the ground. But when you stand next to the painting and look at her perspective, you see this tunnel going off into oblivion. It’s like a digital death. In terms of a Klein bottle (as in Alpha), that tunnel becomes the outside and that’s the basic structure I used for the two paintings.’

What was the impetus behind your Clone series and exhibition?

I wasn’t looking at scientific areas of cloning because I don’t know enough about it to comment. Instead, I thought I’d look at some of the cultural connotations. What I was getting at, and what I tend to do in all my work, is analyse those moments where you are inevitably brought face to face with the metaphysical – things that aren’t quite explainable by rational means. One of the scary things about cloning is that it brings up the archaic idea of the existence of the soul. As soon as you decide to clone a human, then if there is such a thing as a soul, what happens to it? Do you get an “empty” person? I was looking at the fear of having to deal with those questions in a society that doesn’t like to discuss ideas of that nature any more.

There is a lot religious imagery in your work. I suppose that’s ironic…

It’s actually quite earnest, which is a bit of a shock, I know. I realise it’s not too “cool” to talk religion these days, but when it comes to things of that nature, I’m not church-going but I do feel a little religious. I had a Catholic upbringing and that’s fucked me up forever. There’s no irony there! I really do think that today we wall that stuff off: it’s been part of us forever, and all of a sudden, in the last 50 years, we’re doing away with it.

You can’t escape those metaphysical yearnings. They are always going to be there.

You said it – “metaphysical yearnings”. I think it’s silly to define it in terms of really strict boundaries that make different religions go to war with each other. Those metaphysical yearnings are within all off us.

You paint human subjects quite a bit. Do you perhaps talk to these humans first and get an idea of their interests, letting that be a springboard to the final artwork?

I used to, but more and more I’m using my subjects as protagonists. When I started doing this type of work, it was very linked to what the subjects were on about. In fact I was constructing the paintings from the question posed to the sitters – “What is it you most desire?” – and using that to construct the whole painting. But now it’s shifted; with the protagonists in the Clone series, I’ve got more specific ideas of what I want them to do and how I want them to pose and how I want the painting to look.

Often, the people who write about your work see your cloning theme as filled with dread and doom. But isn’t it more playful than fearful? Although you touch on some heavy topics, I can’t help but see an element of fun there, as though your subjects are amused (as well as baffled) by the possibilities presented by their doppelganger.

I’m glad you picked up on that because I’m not that serious a person! Basically, I get bored very easily and like to introduce different things all the time, different styles and themes. I look to people like Charlie White, who’s completely nuts!

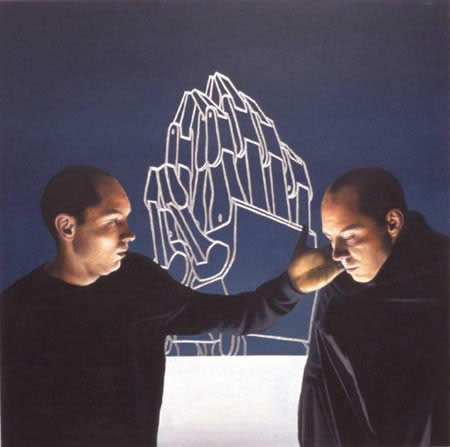

The Big Prayer (2002) 1200 x 1200.

‘Here’s Dave – actually two Daves – face to face. One is incredulous, while the other looks like he’s just come out of a lab. In the distance, the perspective is no longer anamorphic; giant robotic hands pray in the background. It makes all sorts of references to artificial intelligence and the notion that the metaphysical will endure as long as humans are around (or their clones).’

That leads me to the boring, but inevitable question: what are your main artistic influences?

I like so much stuff – that’s really hard to answer. I mean, I like the really crazy, scary art like Paul McCarthy and Charlie White. I like minimalism and a lot of the abstract painters, but not so much the American stuff. Going back I just love Caravaggio. I think he’s the stand-out painter of all time. He did things that no one else was willing to do at the time; he truly took risks and was exceptionally gifted. He’s amazing! Other influences: graphic design, architecture, good web design, wire frame aesthetics, 3D modelling. A lot of street style, a lot of graffiti, although not overtly. I don’t make graffiti but I love the way it can look; Futura 2000 is the obvious example.

How viable is it to make a living as a painter in Melbourne?

It is do-able. You have to work very hard and I think Melbourne is a pretty picky art market. Your work has to be of a critical quality. Some people think it’s all about schmoozing, as with anything, but I don’t think that’s the case here. Certainly who you know does help, but the great thing about Melbourne is that I really do believe it is about the work. And if you’re in it for that, then you can actually make a slim living from it.

Does Melbourne have a supportive infrastructure and galleries who’ll give new painters a go?

There is the support, but I think there’s also a culture of having to prove yourself a bit, which is fair enough. I’ve actually gone out and curated shows about my ideas and my painting and got the ball rolling. And that’s when people pick up on you, because they see you out there trying to do something.

What’s the state of art funding in Melbourne or Australia? How would you improve it?

I’d get rid of the Liberal government, for starters!

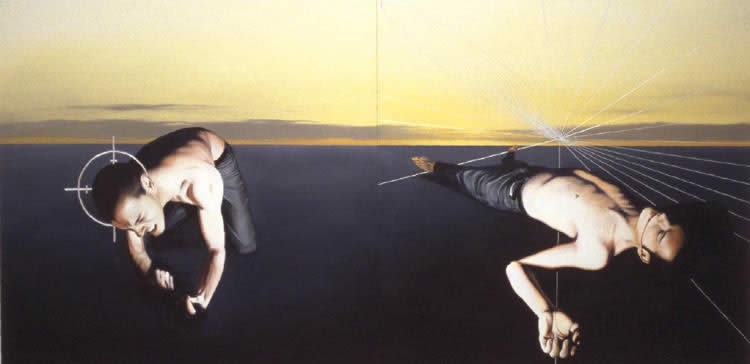

Saints & Sinners (2002) 2400 x 1200.

‘Here’s Chris Bond, an exceptional Melbourne artist. For the photo shoot, Chris brought in all sorts of props: fake blood, clippers, everything. So I said, “OK, we’ll shave your head in one half of the painting and have you with long hair in the other”. It’s a bit hard to tell here, but if you look at the “Chris” on the left he’s actually clutching the hair of the “Chris” on the right, so there’s this very strange drama going on. He’s also got this halo like a gunsight, and of course, the anamorphic tunnel going off into the distance. I really didn’t think I could sell this painting, but I did! Which is bizarre, because it’s so confronting, with lots of blood and everything. We had a lot of fun with that shoot – it was really anarchic.’

It’s that dire?

Well, I guess it could be a lot worse; I don’t want to complain. I mean, I’ve done everything myself and I’ve never actually received an Australia Council grant or anything like it (as yet). There could always be more funding, but then again we could be living in Somalia. You’ve got to keep things in perspective as to what we want and what we need. I think Melbourne’s got a pretty well-supported arts community in some respects, but I think extra finding could broaden the interest of art amongst the public.

Do you think visual art has an image problem compared to music or film?

Art has an incredible image problem. You know, the “my child could have painted that” attitude is all-pervasive and it’s not actually true. That’s the stuff you see on the fringes of art and of course it grabs all the headlines. But you know there’s some really talented people out there. Actually, I think that image problem is fading because artists are starting to put a lot more time and thought into their work. And I’ll probably get shot for saying this, but I really think previous generations have been very arrogant towards the public and this has of course created antagonism. Modernism did a lot of good things, but I don’t think paring things down to just the “idea” is enough. Artists dug themselves into a hole – “painted” themselves into a corner, if you will – when they really should have been undertaking more work. But because of that shift in attitude, we’re starting to see some really interesting art involving less talk, less theory.

LINKS

>> Juan Ford

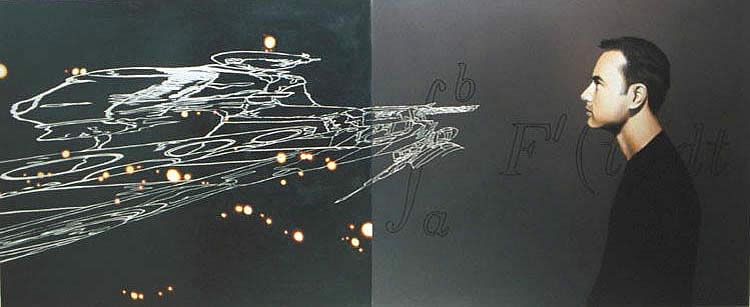

The Akira Equation (2000) 2400 x 1000.

This is Rick. His desire was for more resolve – to be more resolute – so I pictured Kaneda, Tetsuo’s friend in the manga film Akira. Tetsuo is about the most resolute character you could ever imagine so I used an anamorphic image of him standing atop a robotic tank as an image of real resolve.