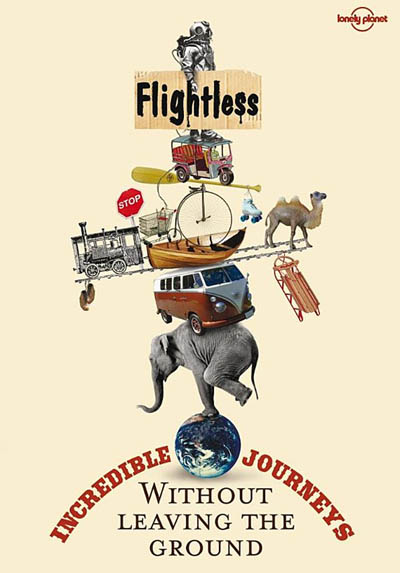

‘Tohoku Dreaming’, originally published in Flightless, Footscray: Lonely Planet Publications, 2008.

The last job they gave me was book-ended by madness.

It began somewhere in the labyrinthine insanity of Tokyo. I was trying to sleep in a tiny apartment, sweat pouring off me in great sheets. I was on assignment for one of the major guidebook publishers and I’d gone barmy from information overload. From reviewing 20 hotels a day. From the language barrier. From asking the same inane questions of hotel flunkies in an insane feedback loop. There was a heat wave and my skin was itchy and damp, mould growing on my pyjamas from the humidity.

I passed out, a slab of meat on a tatami mat.

I felt rough hands under my armpits. Two figures swam before me, hazy in the interpolation of waking life. Faces; the telltale syntax of body language – the shapes took on familiar tones, and I knew.

It was the Company! They’d tracked me down! Would I never be set free?

My commissioning editor, known to me by the code name ‘Jackie’, knelt down beside me.

‘Sellars, wake up. C’mon, soldier,’ she whispered, calm and businesslike. ‘You’ve got work to do. Real work!’

Jackie’s boss, Rachel, stood at the doorway. ‘Yeah. Real work,’ she hissed, barely containing her revulsion.

They dragged me to the bathroom, forced my head under the shower, turned on the cold water. Rachel shook her head.

‘We’ve got kids on file who’d sell their grandmother to do your job.’

‘Yeah. Your job.’

I began to scream and they took it in turns to slap my face.

‘Wake up, soldier!’

I forced my eyes open…

…and this time I was awake for real. And I really was in a tiny Tokyo apartment sweating on a tatami mat in mouldy pyjamas, but everything else – just a nightmare. Shaking, I went to the kitchen and poured red cordial into a glass. Two women were in the living room. My blood froze. Not the Company! But I recovered, pushing through the pea-soup of half-sleep and out the other side: living in Japan…from Australia…expat friends…Nancy and Clare! I was staying at Nancy and Clare’s place.

They were watching the Super Terrific Happy Hour on TV. I excused my dishevelled, lunatic appearance.

‘Bad dream…’

And then the room began to shake. The red cordial leapt organically from the glass like sentient alien blood in the film of The Thing.

‘Earthquake!’ Nancy yelled, bolting for the door. But all I could think of was those moronic public-service announcements from the 50s, instructing schoolchildren to ‘duck and cover’ in the event of nuclear attack.

I scrambled under the kitchen table, gesticulating like a jelly-wrestling octopus.

‘No, under here! DUCK AND COVER!’

The others came and we stared wildly at each other, breathless, on all fours under the table. Scared numb out of our wits. The floor gently rippled every few seconds. Then it buckled crazily.

Clare took control.

‘Stuff THIS! Everybody out!’

We ran outside to the balcony, which was swaying like a flimsy hammock. What to do? Wait for it to snap like a twig? Run for the street and risk death by falling concrete? Or get back under the table? The building was shaking so much my vision was blurred, like in sci fi films when stars smudge in hyperspace. Everything was distended, the balcony like sponge under my feet.

Panic set in: we were out of commission, couldn’t speak or move. And then it was all over, with no structural damage to the building – or us. I tried to light a cigarette but my hands shook so much I dropped it. I couldn’t even see my hands – my vision was still in hyperspace. Slowly, ever so slowly, we found our minds and went back in. The quake’s epicentre was in the ocean, and tsunami warnings were on every TV channel.

Clare translated.

‘Big tidal-wave warning in Tohoku. That’s where you’re off to, isn’t it?’

It was. I had an assignment to write about Tohoku, known as the ‘Japanese deep south’ (even though it’s up north), an agricultural, mystical ‘back country’ tarred with fear and disdain by city slickers. The guidebooks painted a grim picture, caricatures of stultifying industrial towns and unwelcome foreigners provoking barely controlled hostility in the locals. But I took the job because Tohoku reminded me of my childhood. As a kid I was fascinated by the Australian island state of Tasmania. Back then, Tassie was considered fit only for sheepshaggers and inbred mental defectives; these days it’s as hip as the bony projection of a femur. But I loved the old Tasmania – remoteness was very romantic to a boy as painfully shy as I was. Tohoku is like Tassie from the 70s: unloved, forgotten, ignored. Ridiculed by stand-up comics.

Another bonus: there would be no flying involved, which, as a travel writer, I’ve increasingly come to hate. Everyone says travel writing’s a glamorous life. Not when you’re waiting in a queue at Heathrow for four hours to have your underwear swabbed for explosives, dodging security, surveillance, crowds – the sheer grind of mainstream travel. In any case, is there anywhere left to go? It seems like the entire planet has been commodified and quantified, buried beneath a spider web of budget flight paths. Except for Tohoku; it’s untouristed. No one rates it.

Plus, I like ghost stories. And Tohoku has plenty of those. It’s as spooky as Botox.

The next day I had to leave; my schedule was tighter than Madonna’s forehead. I hugged my friends.

‘You must learn proper earthquake procedure,’ I told them. ‘For all I know, you need to fashion tinfoil hats to protect against harmful gamma rays erupting from the Earth’s crust. Make sure you find out: Japan can trick the unwary.’

And with that I caught the bullet train north, on my way to Aizu-Wakamatsu, a small town with a reconstructed samurai castle in Tohoku’s Fukushima prefecture. On the train I sat next to a very tiny lady who told me she was from Akita prefecture.

‘Our skin so soft, Akita girls,’ she told me. ‘Softest in Japan…’

I didn’t dare touch her to find out. She seemed not of this world, her skin not so much soft as translucent.

I arrived late at night and I was lost; I had no idea where Aizu’s youth hostel was. The streets were empty save for a gang of scrawny kids, their modishly long hair spiked to the heavens like deep-space telemetry. They seemed to live in the train station.

‘Sumimasen,’ I whispered. ‘Youth hostel?’

The gang’s leader stared at me with obvious contempt. Baring his teeth, I thought he was going to bite me. Then he snapped his fingers and the entire mob, en masse, reached for black hoods to pull over their faces, blocking out their exposed flesh. Moving towards the station, they merged seamlessly with the shadows…and maybe the afterlife. I never saw them again.

An elderly fishmonger walked by. He wore rubber boots, a white smock and smelled like he’d been kissing carp all day long.

‘Youth hostel?’ he said, pointing at his Toyota van.

‘Hai!’ I exclaimed. ‘Youth hostel! Arigato gozaimasu.’

He patted my head and threw my bags in the back of the van. We drove in silence for 20 minutes and I couldn’t be sure he was awake, so still and quiet was he. Actually, I thought the van was guided remotely and he was plugged into it telepathically, but it was just a super-advanced GPS system doing all the guesswork. Then suddenly the van stopped. The fishmonger’s mouth moved.

‘Youth hostel.’

I clambered out and was greeted by the hostel’s manager, another old guy, as leathery as a samurai’s undershirt. He spoke a few words to the fishmonger and received a wrapped fish in return. Aizu was desolate, bleak, as silent as a tomb. I even saw a tumbleweed rolling down the hill (or the Japanese equivalent: a cherry-blossom branch?). The fishmonger drove off and the manager snaked his arms around my shoulders.

‘Sake.’

‘Yes, sake.’ I was tired and grumpy. Getting drunk was the only way.

We tossed back Japanese rice wine in the dining room. The manager said he loved his town, was proud of its fighting qualities.

‘Aizu is samurai spirit.’

He told me about the Byakkotai, Aizu’s famous samurai who committed ritual suicide during the Boshin Civil War.

‘Aizu-Wakamatsu, authentic samurai tradition! Mussolini!’

‘Mussolini was a samurai?’

‘Mussolini love Byakkotai! Aizu bear his name!’

He told me that Il Duce, smitten with the story of the Byakkotai, had commissioned an ostentatious monument to their memory that commands the summit of Aizu’s Iimori mountain. I wasn’t impressed. I’d been trained to despise fascist dictators, but before I could argue the toss, the old man had passed out, snoring on the floor. I went to bed.

The wind that night was insane. It screamed and whistled and battered the wooden A-frame of the hostel and the windows and the doors, invading my dreams so that I imagined I was being chased by a huge, hissing, mutant kitten with lantern-green eyes and really nasty, sharp claws.

I was a mess the next morning.

‘Bad dream,’ I told the manager. ‘The wind; big cat…claws…sharp!’

He laughed, telling me that Japan had been hit by ‘Typhoon No. 10’, leaving 34 dead on the coast.

‘Don’t cry like a girl!’ he scoffed. ‘Japan hit by ten typhoons this year. Only your first!’

A ‘girl’, eh? And yet I could see myself hanging tough with this Japanese Hemingway for weeks on end, trading good-natured insults about each other’s masculinity, but I had to push on. Guidebook writing is relentless. There’s no time to be a tourist or to make friends, and your only companion is the quick and brutal clock.

From Aizu I took more trains, aiming for my next stop, Tono, a town in a rustic valley with a strong animist culture that forms the heartland of Tohoku lore. Inch by inch, I penetrated deeper north; the bullet trains only go so far and then you must get the country service. To get to Tono, I had to wait four hours in a town I never knew the name of. I had no provisions and no money, and there was no ATM My minimal Japanese was not good enough to ask for schedules or to gather any shred of information that would confirm I had landed on the right planet. I still didn’t know where I would end up. The only way to know for sure was to wait for the train and see where it took me. But I had no idea when it would even arrive. It could have been that night or the next day, the next week, so I was forced to pass the time by pretending the kanji characters on the train station’s signage were Space Invaders lasering my eyes out.

I passed out on a bench, dreaming about aliens trying to read my mind. Arnold Schwarzenegger was in the dream, and he told me to wrap something moist around my head to block the aliens’ super-powerful telepathic tractor beams that would wrench the thoughts from my skull like ripe fruit…

…when the train came it was midnight, and fifty Japanese raced onto the platform from out of nowhere. Their noise woke me from my deep slumber, and I was most surprised to find a wet towel wrapped around my head. I tried to act natural, casually tossing it aside, and followed the throng on board.

Eventually I arrived in Tono, in the dead of night. Eerie mountains ring Tono and at night its still, inky black atmosphere can give a person the fear.

I checked into a small hotel and slept like a dog. In the morning, the manager sat all the guests down.

‘Tono is kappa territory,’ he told us.

‘I know about kappa,’ I piped up. ‘They’re water spirits. Sandy from the TV show Monkey was a kappa. They’re really dumb and they can be easily fooled.’

The manager glared at me. His burning gaze was a red-hot poker giving me a frontal lobotomy free of charge.

‘You’re the fool. Never go near one. They’ll pull your intestines through your anus. Just for fun. Then you can’t shit and you die.’

A bespectacled Japanese geek in red motorbike leathers turned to me, peering over his glasses.

‘You know Osira-sama? That’s the best Tono legend.’

He looked to the manager for approval; the manager nodded sagely.

‘Osira was once simple Tono farm girl,’ the motorgeek explained. ‘She had horse she loved so much, they get married. But father is disgusted, hangs horse from tree. Sad girl clings to her lover, but father beheads the horse. Then girl and horse fly to the heavens to become gods. She becomes Osira: Japanese symbol of fertility.’

I was confused, unsure how bestiality begets fertility. But I didn’t want to lose face. Instead, I was the one nodding sagely.

‘Ah yes. I once saw the Jerry Springer Show: he had a guest that married a horse.’

The biker geek smiled. He actually appeared to pity me.

‘Ah, yes. But Springer never has any answer.’

Which was true – all Springer can do is react to extreme situations. He never solves a problem or offers any solution. And they made an opera about him! Overrated.

After a tour of the town, I decided to get out of Tono. The legends were just too much and they all believed in them. They even tried to tell me there were chameleon foxes in the mountains who were as big as ponies when seen from the front, and as small as a human baby from behind. Besides, the clock was ticking – my deadline loomed like a horse about to make love to a farm girl.

I took the bullet train further north. This time I sat next to a scientist from Niigata who claimed he had invented a revolutionary new pizza base – made from baby squid. I made my excuses and went in search of empty seats, leaving him to his reverie.

‘Squid, baby squid. Plentiful. Cheap. Fullest flavour, superior texture…’

Alone at last, I marvelled at the miracle of engineering that is the Japanese bullet train. You can’t tell how fast these things move from the inside, so smooth and integrated is the ride. There are no bumps. The carriages barely make a sound. At 300km/h, you may as well be time travelling into the future: one minute you’re here, the next second you’re there. I watched Japanese boys break dancing in the aisle, businessmen asleep with drool on their chins. Tea ladies sold eel and sushi and I drank beer and we were all floating on air. The Japanese bullet train is a mystical experience.

Then suddenly there was change, the airlocked stasis broken by a robot voice announcing the next stop: Morioka. I sprang into action and leapt off the train. For I knew what Morioka signified: wanko-soba. I’d heard so much about this ritual, which derives from the feudal era, when the peasantry’s crops were decimated and there was only soba noodle for dinner. Because that’s all they had, the peasants felt compelled to make it the best soba ever and they were mortally offended if guests said ‘No more,’ even if they were stuffed to the gills.

I dumped my bags in a coin locker and headed directly for Azumaya restaurant, near the station – best wanko-soba in town, said the guidebook.

I must have been an obvious mark, because the second I stepped inside five waitresses raced over. One pulled up really close. She placed a ‘special wanko-soba smock’ over my head and explained the rules.

‘I bring you 15 bowls filled with wanko-soba. You must eat them.’

Once I was on the last bowl, she would bring out 15 more, filling up that last bowl one by one with this new round of 15, even if I pleaded with her to stop. One I got through that, she would bring out 15 more, then 15 more, and on and on. I could only get out of it by placing a lid over the bowl, but if she beat me and refilled it, I had to eat it.

‘It’s only plain noodle,’ she urged. ‘So eat some side dish. But leave room for wanko-soba!’

No problem, I thought: the bowls were more like oversized cups and 15 equalled a standard noodle box.

Everyone in the packed restaurant stared as I easily devoured the first round. There was even some light applause.

My waitress bellowed, slamming another tray down.

‘Eat!’

I got through the second lot of 15, scared of her wrath, but when I flagged on the third lot she changed tactics, trying sweet talk instead.

‘One more bowl,’ she cooed. ‘Do it…for me.’

After the 32nd bowl I wanted to throw up. I went for the lid, but she was quicker on the draw and refilled the bowl. I had to eat it. That was the rule. After five more bowls I again went for the lid but I was as punchy as Rocky Balboa. Again, she beat me.

Some guy next to me snorted derisively, and she turned to share a conspiratorial smile with him. Seizing my chance, I slammed the lid home, slumping backwards, exhausted.

‘You’re very brave man,’ she said. ‘But not good enough for wanko-soba. Record is 500 bowls. Not even close!’

I left, dejected, and checked into a capsule hotel. The following evening, I caught the night bus back to Tokyo. My work was not finished, but already I needed a break from Tohoku; I’d be back but I needed to rest and see my friends.

Beside me on the bus was a young Japanese who kept staring at his reflection in the window, zigzagging his head from side to side and up and down like an electrocuted bird. It was as if he was trying to catch himself out, trying to trick his reflection somehow.

We arrived in Tokyo at 6.30am. Bird-boy was greeted by his girlfriend, who was wearing a costume that made her look like Edward Scissorhands, complete with some kind of mechanical claw attachment and what looked like frosting on the outfit’s shiny black shoulders. She looked like she’d just stepped out of a meat locker.

I, on the other hand, had no immediate place to go and no one to see. I was due to meet Nancy and Clare at 5pm, but desperately needed sleep in the meantime.

Two girls walked past, both dressed as Little Bo Peep, one in a flowing blue dress, one in a red dress. Both wore bonnets, extravagant wigs of golden curls and outlandishly large, fake eyelashes.

I caught their eye, remembering that in the best Japanese fashion, all the kids go to Internet cafes for a nap after a big night out.

‘Sumimasen,’ I stammered. ‘Internetto?’

Incredibly, they were brandishing crooked sheep-herding staffs, which they used to point me in the right direction. I thanked my little shepherds and took off.

At the Internet cafe I slumped into a comfy leather seat. Sweet sleep, at last…until a loud American voice.

‘Hey dude!’

A stocky man in a suit with a bowl haircut leant over from the adjacent cubicle.

‘You American? English?’ he bellowed. ‘Just cruising round?’

‘Australian. Just back from Tohoku.’

‘Tohoku! Say, what’s that island there? Monkey Island?’

‘Never heard of it.’

He was fit to burst.

‘Oh man. They’re breeding super bionic monkeys there! Some kinda crazy research facility. Hey. And I’ll tell you this: Tohoku is fulla ghosts. You like Japanese castles?’

‘Yeah. Aizu’s.’

He looked distant, melancholy.

‘Man, I saw a ghost in a castle. Little samurai dude.’

He held his down-turned palm four feet off the ground.

‘Only this big! Jesus! He ran straight at me, waving this huge freakin’ sword. But I hurdled him…and…and he disappeared.’

He let it sink in.

‘So, you like Tohoku?’

‘Look, I love Tohoku but I feel a little strange right now. I haven’t had any sleep, I’ve been on too many trains and buses, and I need to catch more to go back and finish my work. And I just saw two girls dressed like Little Bo Peep.’

He grabbed my shoulders, fixed me with a level stare.

‘Hey, don’t sweat it. You don’t need trains to travel around Tohoku. You just need this,’ he said, tapping his temple.

‘Just remember,’ he droned. ‘It’s only a dream…’

The next time I opened my eyes I was back home, work finished, madly writing up my assignment and emailing it to Jackie.

And I’m telling you the American was wrong: this is a true story.

BIO: Simon Sellars is a freelance writer based in Melbourne, Australia. In 2004 he travelled to Tohoku on assignment for Lonely Planet. Or did he? As his bio no longer appears in LP’s latest Japan guide, it’s becoming increasingly harder to tell. Maybe the American was right, after all…